ARTICLES

Journey through grief and love during the period of this pandemic

When Moses arrived at the flames of fire from within the (bramble) bush, he took off his sandals because God told him that he was standing on holy ground. When we relate to each other about our journey during these challenging times of the pandemic, we are treading on holy ground. It is therefore with utmost respect that I converse with you about grief.

During 2020 / 2021, our country and continent were deeply affected by Covid-19, and globally, millions of families were plunged in grief. The loss of loved ones who died confronted all of us, and we will most probably experience this more than once during these times. In fact, it is alarming that we are so ill-prepared and ill-equipped for grief, while it is inevitable for us to go through this experience more than once in our lifetime.

To experience a loss during these pandemic times, poses its own challenges. A loss is followed by intense painful emotions, called grief. The more significant the loss is, the more intense the grief is. Grief is unpredictable, unsettling, unnerving and messy.

People are often asking what the time span of grief is. The people who ask me the question about grief’s duration are often the newly bereaved, wishing for life to be as it once was. The answer is easy: For life! Things cannot and will not ever be exactly as they were – because the bereaved and his or her world has changed.

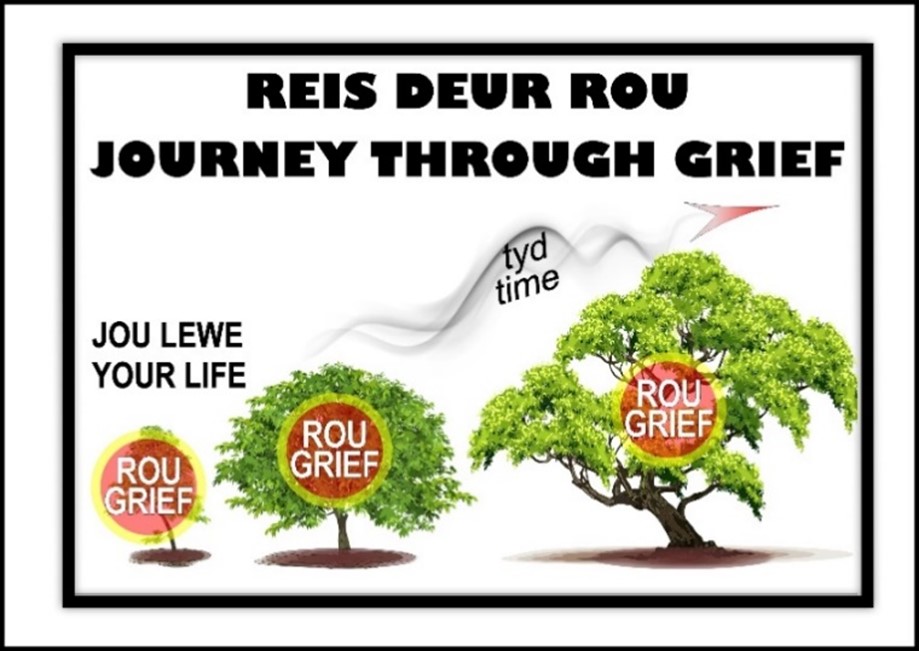

Look at the picture with the trees:

At first the pain of the loss is so intense that it captures the biggest part of the bereaved’s life. It takes everything out of you just to breath. Sometimes you wonder if another breath is possible. How could the world continue spinning after such a loss? The depth and breadth of the loss is unfathomable, and its full impact is never realized immediately, but only gradually and over time. The mind tries to protect us from near-lethal shock and a type of emotional anaesthesia often ensues so that we may feel as if we are in a movie or operating in slow motion. As the shock of the loss gradually withdraws its numbing veil, an indescribable pain arises from the innermost pit of our bellies. But as times passes by, and the bereaved accepts the fact that the loved one isn’t a part of their daily life anymore, they adapt to their environment without the loved one. The tree keeps on growing, and although there is still grief, it becomes part of the bereaved’s life and does not dominate their total life anymore.

That doesn’t mean that the bereaved has forgotten the loss or has left it behind. We lost a baby boy and sometimes when I see a baby boy, my heart aches again, and then I am thankful because I haven’t forgotten him.

The last tree indicates that the grief is integrated, implying that the bereaved has excepted the death of their loved one. There is a new interest and involvement in life, and less obsession about the loved one. T

hat does not mean that we arrived once-and-for-all at healing. Grief is an unending long journey.

No pain is as intense as the loss of a loved one, but I want to inspire you by informing you that our bodies are wired to cope with loss. Our bodies activate different emotions when we experience loss. These emotions are functional because it helps us to work through our grief process. Emotions are short-lived with a duration of a few minutes or hours at a time. Different emotions come and go. One person related: “I was stunned by the different levels of anxiety that I experienced with the death of my loved one, but I was also astonished about the fact that my pain often subsided. Sometimes I felt so sad that I thought I would get a heart attack, but just a moment later I was making small talk with someone, laughing as if nothing was wrong. This was strange.” The short-lived nature of emotions is important and has important implications for the process of grief.

The most dominant emotion when we are mourning, is sadness. Sadness occurs when we react to the unwelcome information that we have just lost someone who was very important to us and that there is nothing that we can do about it. It reaches us through a telephone call at midnight, or the doorbell that rings when you expect it least. Sadness shuts off our biological system in order for us to withdraw inward. Suddenly we experience everything in slow motion. Research indicates that sadness focuses our attention on our inner self, taking stock of our inner self. Our sadness helps us to more accurately recognise our capabilities and actions and to reflect deeper and more effective about our inner self. In this way it guides us to adapt to an environment where the person whom we have lost, is physically absent. This helps us to accommodate the loss and the pain.

When we feel sad, we also appear physically sad. Our faces are hanging, our eyebrows are narrow and higher than usual and forming a triangle, while our eyelids are narrow. Our jawbone is also hanging. Our sadness and pain are clearly visible in our bodies. Our heads are hanging, and we cover our faces with our hands. Our sadness is evident in our appearance, and others can see it and realise that we need help. This evokes their empathy and support. They put their arms around us and give us a hug. Crying releases endorphin which reduces pain. It is like morphine. This is the reason why one feels emotionally better after one has cried.

Anger is another emotion that is often experienced during the grief process. It is also functional in assisting us to work through our grief. Anger appears when we find that someone else wants to cause us harm or damage. We reason that this person was insensitive or unfair towards us. We sometimes experience anger at the situation, or at God, or the medical personnel. Sometimes we are angry at the deceased, feeling that they have deserted us. We are angry because s/he did not want to take the medicine, or s/he did not want to go to the GP sooner. The function of anger is to strengthen you for the battle that lies ahead and to help you to develop a feeling that you will be able to survive on your own.

Both these examples of emotions indicate to us that it assists the bereaved in working through the terrible pain of loss. The fact that emotions are short-lived, therefore not persisting very long, makes the grief tolerable. Physical pain like toothache is persistent, but grief is like a bomber that circles above the target and every time the target is in sight, they drop the bombs. This short duration of emotions makes grief bearable. This is the wonderful human capability to alternate one’s sadness with short moments of joy and gladness. Grief is bearable because it comes and goes in waves, without shedding the full package of grief on us. One moment we focus on the pain of the loss, while just a little later we laugh at a joke told by one of our children. At that moment we feel temporarily better before we continue with our grief process. This also affects our bodies. We inhale and exhale all the time. We cannot inhale and exhale simultaneously. This is why we breathe in cycles. Our muscles contract and relax. We sleep and then we are awake. We cannot rest and be wide awake simultaneously. Even when we are sleeping, we are altering between deep sleep and light sleep. Our body temperature rises and declines. It is impossible to be physically involved in contrasting activities. This oscillation between emotions makes the grief process more bearable for us. It is impossible to simultaneously focus on the reality of our loss and our environment around us. This also happens in cycles. Grief will therefore never overwhelm us because it is not constantly there. Research has indicated that this bouncing back from intense grief to a better emotion, is characteristic for a bereaved person. A person is wounded by the loss but is able to regain their balance and move on with life and even fall in love again. As time goes by, the grief calms down, and the bereaved moves slowly but surely back to normal. This bouncing pattern helps the bereaved to survive the pain caused by the loss. In time, the bereaved regains control over their sadness and becomes able to choose when to mourn and when to talk to family and friends about their loss. As time goes by, the sadness calms down and the bereaved returns to a normal life. The longing for the loved one diminishes little by little. Grief is like a light that becomes dimmer and dimmer. Although it becomes dimmer, it never goes out totally. There will always be a flickering….

To process a loved one’s death is a very difficult and painful experience. Amidst this pandemic, there are even more challenges related to the loss of a loved one.

During the pre-Corona era, a certain family lost a loved one. The farmer contracted multiple burns in a fire on his farm, and his people hurried him to Unitas Hospital. While the ambulance was on its way, his family was waiting for him at the hospital. His daughter and sister sat next to his bed in ICU for two days during the day. That Sunday morning at six o’clock, the hospital phoned his daughter and requested her that the family had to come and say goodbye. When they arrived, the personnel pushed his bed aside in ICU. His sister and her children and families, as well as their children took hands around his bed and told him how much they loved him and how they were going to miss him. Each one had a chance to say goodbye. Then his son read from the Bible and prayed, and they all sang together while he was dying. All of them went to his daughter’s house for the rest of the day. There they ate some food and told anecdotes about this man. Three days later they sat together with his friends and congregants in a church which was filled to capacity to bring him their last honours. His family cried in each other’s arms and comforted each other with hugs. The pain of this loss was immense but short-lived. I would know because I was his daughter.

I chatted with a woman who lost her husband in the Corona pandemic. Her husband got ill and she took him to hospital, just to find out that he has contracted Covid-19. The next night she received a call from the hospital, informing her that her husband has died and that she had to remove the corpse within half an hour. In the middle of the night, she had to find an undertaker. She felt so bad that she was not there for her husband during his last moments. She was just in time at the hospital to see how they took the body away, wrapped in a lot of plastic, keeping everybody away from them. She could neither see nor touch him for the last time. She was deprived from saying goodbye to him. This was the beginning of her nightmare. Nobody ventured it close to her as they were afraid that they would contract the virus. She went for the test and the outcome was positive. Days filled with fear lay ahead: She was so afraid that her symptoms would worsen and that she would also die. Friends and family dropped food at her gate. Her children were overseas and could not come and visit. She was forced to mourn on her own, distanced from other people and hugs. In her darkest hours there was nobody to comfort her. She was so angry, but she did not know for whom to be angry.

During the next month, another four family members of her would die of the Covid virus. She has also lost her job….

People who are dying of the virus spend their last days either in hospital or in an old-age home, separated from their family. Their loved ones must mourn for the loss without the comforting arms of family around them, attending the funeral of the deceased. Due to the risk of contracting the virus from someone, the person who has the virus, mostly dies while being separated from their loved ones. The loved ones who are mourning without family or friends around them, mostly suffer from posttraumatic stress disorder. The survivors are shocked by the circumstances in which their loved ones died. The sudden decline, the sudden death, and the impossibility to be there till the end, just make the pain colossal. Lockdown periods, masks, and isolation cause the normal time of grief to be a nightmare. Families are not allowed to mourn in the usual cultural and religious ways they were used to.

Often someone from the hospital phones me, telling me that a patient has died. Most of the time the person does not know the family and only has partial information about the last moments of the deceased. As the family was not there when the person died, chances are that they have the perception that the person did not die. This then becomes the reason why they are unable to process the death. When we are not there when a loved one dies, we are struggling to process the death because we have to form an idea of the last minutes of that person. Was my loved one scared? Was s/he very lonely? It makes your struggle all the more difficult when you were not at your loved one’s side when s/he died. This could also make you feel guilty. Although you were not allowed to be there, you could feel guilty because you have the conviction that you should have been there. “I should have thought sooner that s/he was ill. I should have realised that s/he needed help.” Many people feel guilty because they think that their loved one contracted the virus from them and therefore they are guilty of their loved one’s death.

The period of grief becomes a separated and excruciating time without people who bring containers of food to your kitchen, and people who hug you or drink a cup of tea with you. The bereaved is feeling desolated and alone. Routines and rituals that would normally bring comfort, are not freely accessible, which could increase the feelings of isolation and loss.

On top of that, many households in South Africa are experiencing a loss or illness, and they just don’t have the emotional energy to render assistance to others. The pandemic has caused most of us to be distressed and impatient. Those of us who already had Covid, are struggling with the after-effects, like depression, confusion, insomnia, and panic attacks. In many households, the breadwinner has died, which carries more anxiety, and which complicates the normal intensity of the grief process.

Funerals are big occasions in Africa as the death of the loved one brings people together to demonstrate their sympathy and support to the family. The restriction of numbers at funerals and social distancing are therefore in conflict with the pre-Corona period where we physically gathered with the bereaved and where we were in close contact with them and in their presence. Which 50 people are allowed to attend the funeral? People who attend your wedding are for ever part of your life, and in a strange way this is also the case with people who attend a funeral. People have always come from everywhere to attend a funeral. They were sharing stories and anecdotes about the deceased, in this way keeping the person alive in their memories. At this stage we are deprived of that privilege. Virtual funerals are not worse than personal funerals, but it is very different. In any case, this is all we can do right now, so we have to make the best of this scenario.

2. Coping with a loss

In order to heal you must mourn. There is no “one-size-fits-all” formula to cure the soul. Everybody mourns in different ways, depending on the person and the situation in which they are – their personal circumstances. Everyone of us will have to find our personal way which will lead us away from our grief and despair to healing. Others may tell you that it’s time to “move on” or that this is “part of some bigger plan” and some may avoid you or pity you. But you have earned this grief, paying for it with love. You have owned this pain, even on days when you wish it weren’t so. You needn’t give it away or allow anything, or anyone, to pilfer it.

-

Be Gentle with Yourself

When your life has been shattered into a million pieces, you need to take it slow. So be very gentle with yourself. -

Creativity

One suggestion is to write letters about the emotions that go through your head. You can also create a painting or a work of art as a tribute to your loved one. Music and poems are also therapeutical – especially poems can be of great comfort. You should also continue with your hobbies which bring you joy. -

Talk to other people

At the time of your loved one’s death you could not fully grasp the magnitude of the loss because it was just too much. Your spirit, mind and body protected you by allowing the truth to sink in slowly over time at a pace you can live with. In telling the story of what happened over and over to different people you are able to know the truth of what has happened. Although you may not feel like it, it is very important to talk to family or friends on a daily basis. In this way, you will release the memories that are building up and keep on repeating in your head. Bereaved ones need others who can enter the abyss with them, sometimes again and again. They need to reach out to someone who is safe, who will not judge, who will not shut down or shun their pain. Telling your story over and over is a path to healing. By doing this, you might also acquire useful insight from people who went through similar circumstances, which will make you realise that you are not alone in this process. One day you will discover that you don’t have the energy, desire or need to tell it one more time, and that is what healing feels like. Make use of social media – the digital platform. -

Experience the pain

When others or we ourselves judge our grief as bad or going on too long, we feel shame that slumps into repression. If others cannot bear witness to our pain, we learn to hide it. We feel that we should not be feeling it. Often people try to ignore the pain by killing it with alcohol or pills. They avoid anything that may remind them of their beloved one. You must be brave enough to turn away from all your soft addictions you cling to in order to stay numb. These soft addictions can be watching endless Netflix stories, shopping, eating to fill the bottomless hole in your heart, relying on prescription medication, kidding yourself by saying they must be okay because “The doctor knows I’m taking them.” The danger of trying to bypass grief is that grief then comes out sideways. Remember, nobody is able to move around grief – you must pass through it. If you don’t pass through grief, you stand a good chance to land yourself in a deep depression. Otherwise, you will get caught in the pain and misery, and become obsessed about the death of your loved one, in this way estranging yourself from your friends and family. -

Cherish Yourself

Rebuild your broken body. Attend to yourself and do exercises, eat healthy food as the nutrients will help your emotional wellbeing. If you are physically healthy, you will be able to handle your emotions better. The general symptoms of grief can have a negative effect on your wellbeing, like insomnia, eating disorders, and anxiety. Physical exercises can reduce your anxiety and help you to sleep better. It is very difficult to eat when you are in a state of shock or grief. And bereaved people don’t see their way to prepare a good healthy meal only for themselves. Self-care can take many other forms than eating and sleeping well. Getting a massage, finding solitude, being surrounded by loving others is examples of being gentle to yourself. For many grievers grieve amplifies during special occasions like mothersday, Christmas, fathersday or baby showers. Self-care means saying no for being at these events if you feel you are not ready. When grieving, we need to give ourselves permission to put our own needs first for a while. -

Routines

Try to return to your normal routines or create a new routine for yourself. It gives you a feeling of normality. There is comfort in routine. Create for yourself a daily routine, which is very important when your sadness is still new because it provides a structure for your day. Make sure that you climb out of bed every morning, that you take a shower or bath and put on some fresh clothes, although you may not have anything to do during that day. -

Grief

Put aside some time for yourself to mourn and don’t let anyone tell you how to mourn or how to feel. Ignore other people’s words like: “S/he is in a better place”, “S/he isn’t suffering anymore”, “Just let go,” “Everything happens for a reason,” or “God needed an angel to tend His garden.” Take your time to mourn. No part of the grief journey can ever be rushed. Plan ahead for anniversaries and birthdays which can cause painful feelings for you. Plan a digital celebration of life where friends and family can share photos. -

Spend time with your Friends

Invest in old and new relationships. Don’t exclude old friends from your life and try to hide yourself from them. Accept as many invitations as you can. - Refrain from making big decisions during the first few months after your beloved’s death

-

Memories

Research have shown that the bereaved people who are able to cope with their loved one’s death, are also able to accept the finality of the loss, and find comfort in the memories of the deceased person. They know that their loved one is gone, but when they think about them, they realise that they haven’t lost everything. The relationship is not totally gone. They are still able to remember specific things and find joy in the positive shared experiences. It is as if a certain part of the relationship is still alive. You will always have a relationship with the people you love. Even after they leave their physical body and die. There is so much power in the memories. Although it seems that we have lost someone for ever, there is still something to cling to and to cherish, and that is the positive memories that we carry with us to defend us against the pain of the loss. As time goes by, we become able to oscillate between the positive and the negative memories. -

Accept being the new person that you have become

An important issue for those whose loved one has died is concern with their own identity. For example, parents whose only child has died often ask themselves, “Am I still a parent?” Siblings may ask themselves, “Am I still a little sister now that my brother has died?” A spouse who spent many of her last years of marriage caring for an ailing husband may find the shift away from the role of caregiver to be more difficult than expected. You will never be the same person that you were before your loss. It is therefore important for you to design your new identity, which could be a difficult process. Grieving itself is a learning process. We learn so much about ourselves in grief – perhaps more than we could ever want to know. Haruki Murakami expresses it like this: “When you come out of the storm, you won’t be the same person who walked in. That’s what this storm’s all about.” -

Keep busy

You cannot dwell on your sorrow or your loss every waking moment. In the first flush of grief, you may feel you cannot control the extent of your suffering. But, you can – with friends, with activities, and a plan that forms a lifeline. -

Coping with loneliness

When a loved one dies, a hole is left that no one and nothing else can fill. You do not have to feel like a victim of your loneliness. You can break through your loneliness in a moment by making one telephone call or speaking one word to another person. Share your feelings with someone you trust, let someone else into your private world. The people around you—family, friends, colleagues, caring professionals, are all part of your support system, if you let them.

My mom died when we were still very young, while we really prayed and believed that she would recover from her illness. After her death, my father made us three children sit with him and read 1 Corinthians 13:13: And now these three remain: faith, hope and love. But the greatest of these is love. Then he spoke: “We hoped that Mother would recover from her illness. She did not. We believed that she would recover. She did not. However, the greatest of everything is love, and we will love her for ever!” It is now 40 years later, and I still love my Mom. You will always love your loved one. Love exists beyond death. Love is not cut off by the loss. It remains. Love is eternal. There is no beginning. There is no end. Your life is for ever changed by this loss, although life goes on. Grief is therefore a way to love and live. For all who love, suffering is inevitable. To love deeply is one of life’s most profound gifts, and the loss of a loved one is one of life’s most profound tragedies. Grief and love mirror each other; one is not possible without the other.